Alisa has a tendency to wait until the last minute before heading out, so by the time we left for the ferry, it looked like we'd miss it for sure. We made a wrong turn, turned around, zipped down the country roads, waited painfully behind someone turning left, had to go slow through the town of Bath, and got to the ferry just as they were getting ready to cast off. They'd already lowered the gate. I saw the ferry workers check their watches, but then they opened the gate and let us come aboard.

The ferry ride was short and smooth. There was an air-conditioned lounge and two observation platforms. We saw an osprey nest with a mother (or father) and young (though the little ones are nearly adult-sized already). We could see the huge PCS Phosphate plant as we crossed the sound. It was a short drive afterwards to the  Aurora Fossil Museum.

Aurora Fossil Museum.

After walking through the displays, we crossed the street and spent 40 minutes looking through a pile of "reject" for fossils and shark's teeth. We found lots of shells, coprolites, and coral.

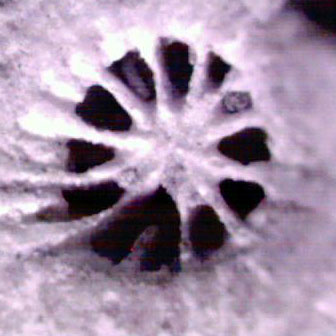

We also found dozens of little shark's teeth. This is one of the smaller ones as seen through the microscrope. I liked the serrated edges.

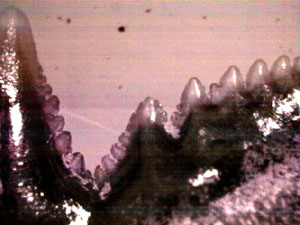

Daniel found the biggest tooth. He had been picking various rocks and asking me if I thought they were interesting fossils and I was just beginning a speech about how he shouldn't just try to take everything, but only to take the best things he found, when he said, "Maybe I should keep this one" and showed me a huge shark's tooth. That cut my speech awfully short.

Afterwards we took the kids to Andy's. ( Here's the menu from another one -- you get the idea, anyway). They served the kid's meals in little cardboard cars. A nice little community place -- it gave me the same feel as Kelly's back home.

Here's the menu from another one -- you get the idea, anyway). They served the kid's meals in little cardboard cars. A nice little community place -- it gave me the same feel as Kelly's back home.

A good day.

I read some literature about the phospate company today while we were at the museum. The scope of the operation is staggering: they essentially strip mine huge tracts of land, clearing off 100 feet of "overburden" (the living soil, plants, animals, trees, etc), then scoop out a layer that contains phosphate rich ore which is then processed using sulphuric acid to all kinds of products: tanker-car loads of liquid fertilizer, but also pelletized animal feed, gypsum, and a compound that is used to flourodate water. The brochure describes water recycling and air monitoring performed to assure environmental protection. They had a list of the kinds of employment opportunities the plant provides: engineers, welders, heavy-equipment operators, secretaries, you-name-it. Here is a huge amount of capital invested: a high-tech factory built, an army of workers employed, a transportation network constructed. For what? To return maximum shareholder value. If you're not returning maximum shareholder value, the money will go to someone who will return the maximum value, right?

In the end, once the economically minable phosphates are exhausted, I expect the plant will close, the people will move on, the land will regrow new communities of plants and animals. What will the long-term costs be? Who will bear them? Who knows. Business is most successful when it can commonize the costs and privatize the profits.

Or maybe some new process will make this plant and its investment irrelevant and the investors will lose their shirts. That's why we let capitalists reap the profits, right? Because they've taken the risk that the enterprise might fail. Profits aren't guaranteed anywhere.

The system doesn't provide any internal checks or balances: it just tries to make money. The system doesn't try to preserve or enhance the qualities of peoples' lives (unless they have a lot of money). If the company recycles water and monitors air quality, it's because there are laws that require them to do so. But the laws can't be too strict, or else the money just goes somewhere else to maximize its return. And increasingly, the money determines who gets elected and what laws get passed. Game, set, match.

I remember we used to do a presentation about the vanishing rain forests when I worked for Living Science. The scenario is presented that the impoverished campesinos slash-and-burn the rainforest to eke out a few years crops on the rainforest soil, which is quickly exhausted and requires them to move on to slash-and-burn more rain forest. At the end of the presentation, the presenter asks the children what we might do to preserve the rain forest. At most schools, the children would discuss providing education and assistance as the means to preserve rain forest. I remember visiting a wealthy, private Jewish elementary school in West Bloomfield or Bloomfield Hills, north of Detroit. When asked what we might do, the students would reliably suggest raising money and using that to finance a public relations campaign to raise more money. Here were kids who knew that, given the system we have, the answer lies not in solving the problem, the answer lies in having enough money. Once you have enough money, there isn't any problem.